Organisational structure: What is important for companies

How to find the right organisational form and set up your company optimally

Whenever people work together, there comes a point when spontaneous collaboration is no longer possible once the group reaches a certain size. This is when a clear division of labour is needed that everyone involved knows, understands and supports. The simplest form of establishing a division of labour is an organisational structure in which clearly described tasks are assigned to specific parts of the organisation. But what exactly does this mean and how can you optimise your company's organisational structure? In this article you will find some answers from our consulting experience.

Organisational structure as an important basis for organisations

An organisational structure defines the framework within which the tasks of an organisation are performed based on a division of labour. It regulates which tasks, competencies, powers and responsibilities lie with which organisational units. This regulatory framework is effective in several respects:

Efficiency gains through specialisation

In an organisational structure, all tasks that an organisation has to perform in order to achieve its goals are mapped in organisational units. This enables employees in each organisational unit to specialise and learn continuously. This results in efficiency gains. There are also advantages for employees: they can build up focussed expertise and have clearly defined tasks.

Functioning division of labour through clear interfaces

Defining clear areas of responsibility for each organisational unit also means that areas of responsibility are clearly described and delineated. Rules for the interaction between organisational units must be defined at the interfaces. This creates clarity about the respective responsibilities and cooperation within the framework of the overarching division of labour.

Clear decisions in clear management structures

The organisational structure also defines the basic logic according to which decisions are made in the organisation that are repeatedly required for the distribution of resources or with regard to the design of the division of labour itself. In organisational structures, management structures are clear about the hierarchical superiority and subordination of organisational units: for example, individual teams that belong to this department are assigned to departments. The department heads manage the team leaders. The assignment of employees to organisational units usually also implies that these employees are managed by the line manager. This allows decisions to be made effectively and, ideally, at the right level.

All in all, the structural organisation thus delineates tasks horizontally and creates clear management structures.

Structure creates clarity

Structural organisations are popular - so much so that they have become the image of the organisation par excellence. They are clear and easy to understand. The classic organisation chart provides a quick overview for everyone involved, whether colleagues, superiors, other teams, departments or external persons. As a result, reorganisations often begin and end with the definition of a new structural organisation.

However, the clarity of structural organisations is usually only a supposed clarity. The complex reality of organisations is reduced to a two-dimensional representation in structural organisations. In this respect, the definition of the structural organisation (also known as the organisational structure) is not sufficient, especially in complex and large organisations, to regulate the interaction of all those involved in a meaningful way.

The necessary addition of a process perspective

As soon as organisations are required to do more than just work (and work off) and achieve Tayloristic efficiency, structural organisations can only guarantee meaningful collaboration to a limited extent. In modern organisations, competitive advantages are no longer achieved through superior efficiency alone, but through skills such as customer orientation, flexibility and innovative strength.

This brings the question of how successfully the various organisational units with their tasks and internal functions can be networked in overarching processes and aligned to common goals into focus. In most cases, a sensible structural organisation is a necessary prerequisite for this, but it cannot replace the complementary process perspective. Structural and process organisations (or, to use an even more common nomenclature: structural and process organisations) are mutually dependent.

The structural-organisational view of organisations must therefore be supplemented by a process-organisational view. A large organisation typically has a large number of processes and sub-processes. The most important end-to-end processes that characterise the value creation of many companies are usually assumed. These include processes such as the innovation process ("idea to product"), the production process ("order to cash") or the sales process ("lead to order").

In addition, it makes sense to also take a look at the so-called supporting processes - such as human resources or finance. However, the term "supporting" tends to be misleading. Depending on the company, the procurement of capital or the recruitment of talent can certainly be a strategic task.

The process view complements (and does not replace) the structural view by helping to recognise certain imbalances in the set-up. In "pure" theory, it even tends to be the other way round: in most cases, the organisational structure of a company will be derived from a rough, possibly intuitive understanding of the process. This understanding states how the most important tasks interlock in order to achieve the desired performance of the organisation: "form follows function". For this reason, when designing the organisational structure, it makes sense to look at how it can best support the flow of the central processes.

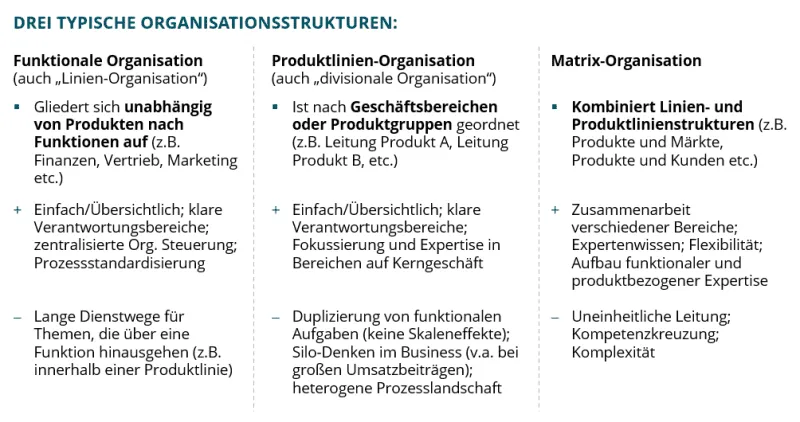

Typical organisational structures

Every organisation is unique in itself. Nevertheless, it has proven useful to name organisations according to their dominant organising principle.

Functional organisations

Functional organisations are structured at the top level according to functional areas. These can be, for example, development, production, marketing, sales and cross-sectional functions such as finance and human resources. In this way, a functional organisation maps the major steps of a value chain.

The decisive advantage of functional organisations is that existing synergy potential can be exploited at the value creation stages. Examples of this include the utilisation of production sites, procurement and the management of human and financial resources. The value chain is also mapped at the top level; it becomes clear which units need to work together to achieve the organisation's goals.

The fact that the most important steps in the value chain are represented at the top level can also be a major disadvantage of functional organisations: Mapping the value chain can suggest a process-orientation, but this usually takes place at too high a level of aggregation for it to be action-guiding on its own. This is because the interaction between sales and production, for example, would only be mapped at management or board level. As a result, conflicts between functions always have to be resolved at the highest organisational level.

At the levels below this, there will be great incentives to optimise the functions themselves, which can be a highly complex task - for example in the production of a car manufacturer with tens of thousands of employees worldwide. In this respect, a functional organisation can encourage the emergence of (functional) silos and make overarching interaction more difficult.

A second, no less relevant disadvantage is that functional organisations tend to be less market-oriented. This means that marketing and sales, and possibly the development department, can quickly become isolated in their efforts to bring customer and market perspectives into the organisation. In capital-intensive industrial companies in particular, the production function can therefore quickly take on a decisive role. Flexibility and adaptability to customer requirements are not advantages from this perspective, but quickly become disruptive factors for an efficient production process.

Divisional organisations

Divisional organisations, also known as product line organisations or divisional organisations, have emerged in response to these disadvantages. They are organised at the top level according to product and/or customer groups (e.g. private customer business vs. corporate customer business).

The decisive advantage of divisional organisations lies in their proximity to the market. They are orientated towards markets and subordinate their working methods to this primacy. At the highest organisational level, products and customer groups have advocates in the circle of top managers. They are in a position to organise the interaction of functions (typically at the level below) in such a way that the organisation's performance for its customers (and hopefully also its economic success) is maximised.

However, this advantage is mirrored by disadvantages that should not be present in a functional organisation. It is in the logic of divisional organisations to duplicate functional tasks in their consistent focus on markets and customers. Economies of scale are not utilised (or are much more difficult to utilise). The functional silo in the functional organisation corresponds to the product silo in the divisional organisation.

A variant of the divisional organisation can be regional forms of organisation that are structured according to regional customer markets instead of global products or customers. This form of organisation is particularly useful if the corresponding markets are highly specific regionally or nationally. One example is most professional service firms, whose dominant organisational axis must be regional or national for regulatory reasons alone.

Matrix organisations

Matrix organisations are the result of an attempt to combine the advantages of functional and divisional organisations: Functional synergies are to be utilised, while at the same time there is a clear focus on markets or products and customer groups.

In order to realise these advantages, the various divisions must work together as smoothly as possible: Responding to customer requirements and simultaneously tapping into functional synergies requires permanent coordination. If everyone involved has the right attitude, this can promote the joint search for solutions and help to find the best way forward.

However, if this is not successful, there are considerable disadvantages: Permanent, at worst ineffective and fruitless coordination leads to delays and sluggishness. Instead of clarity and a joint struggle for the best solutions, responsibility can quickly be diffused. Which scenario is more likely has less to do with the chosen organisational structure, the design of the matrix or its governance (although mistakes are of course possible here); it is often soft factors that determine success or failure. What is needed here is a clear focus on common goals, acting in the overarching interest and the right leadership that emphasises what is common and is equally willing to take responsibility for its own contributions.

Interim conclusion

The advantages and disadvantages of the various ideal types of organisations show that there is no such thing as an optimal set-up. Nevertheless, there are scenarios in which a certain organisational principle is more obvious than others. In addition to the smooth running of central processes, the ability to adapt in the face of the constant change to which organisations are exposed is crucial for organisational functionality.

Structural organisations in times of VUCA and agile approaches

How does the world of VUCA worldwhich is characterised by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity, influence the positioning of organisations? Increasing customer expectations, but also new competitors in dynamic markets, mean that flexibility and the ability to adapt quickly are even more important for the success of an organisation than they were 20 years ago. There is also pressure for change from within: employees are looking for more self-efficacy and want more holistic tasks and more responsibility - as if they wanted to escape the alienation postulated by Karl Marx for early capitalism through an increasing division of labour.

As a result of these changes, new, more flexible forms of collaboration are emerging that are increasingly reshaping traditional organisational structures. Strong leadership, a common focus on overarching goals and a permanent orientation towards added value for the company's customers can help to become more agile even in traditional organisational forms and thus continue to be successful.

Organisations with a strong culture of collaboration and managers who work together can make the necessary adjustments more easily and also work more successfully in agile organisational models. Conversely, the introduction of customer-oriented or agile approaches alone will not be enough to break down strong organisational silos, i.e. the extreme form of a structural organisation.

The radical basic idea: In today's VUCA world, fixed organisational structures no longer work. Above all, they make organisations cumbersome and prevent them from reacting appropriately and quickly to new developments. What is needed instead is dynamic self-organisation within the framework of jointly defined rules. Discipline and transparency are essential to ensure that this does not end in chaos.

The focus of agile working is on the result of the collaboration. The necessary steps along the way determine the cooperation within the organisation.

However, as much as agile principles have been celebrated in recent years, they are not always the right solution and certainly not a panacea.

Scaling agile methods in particular is still a major challenge. It is often necessary to fall back on the classic division of labour and elements of the traditional organisational structure. This combination has led to the emergence of more and more hybrid organisations in recent years, in which traditional organisational structures and agile elements overlap.

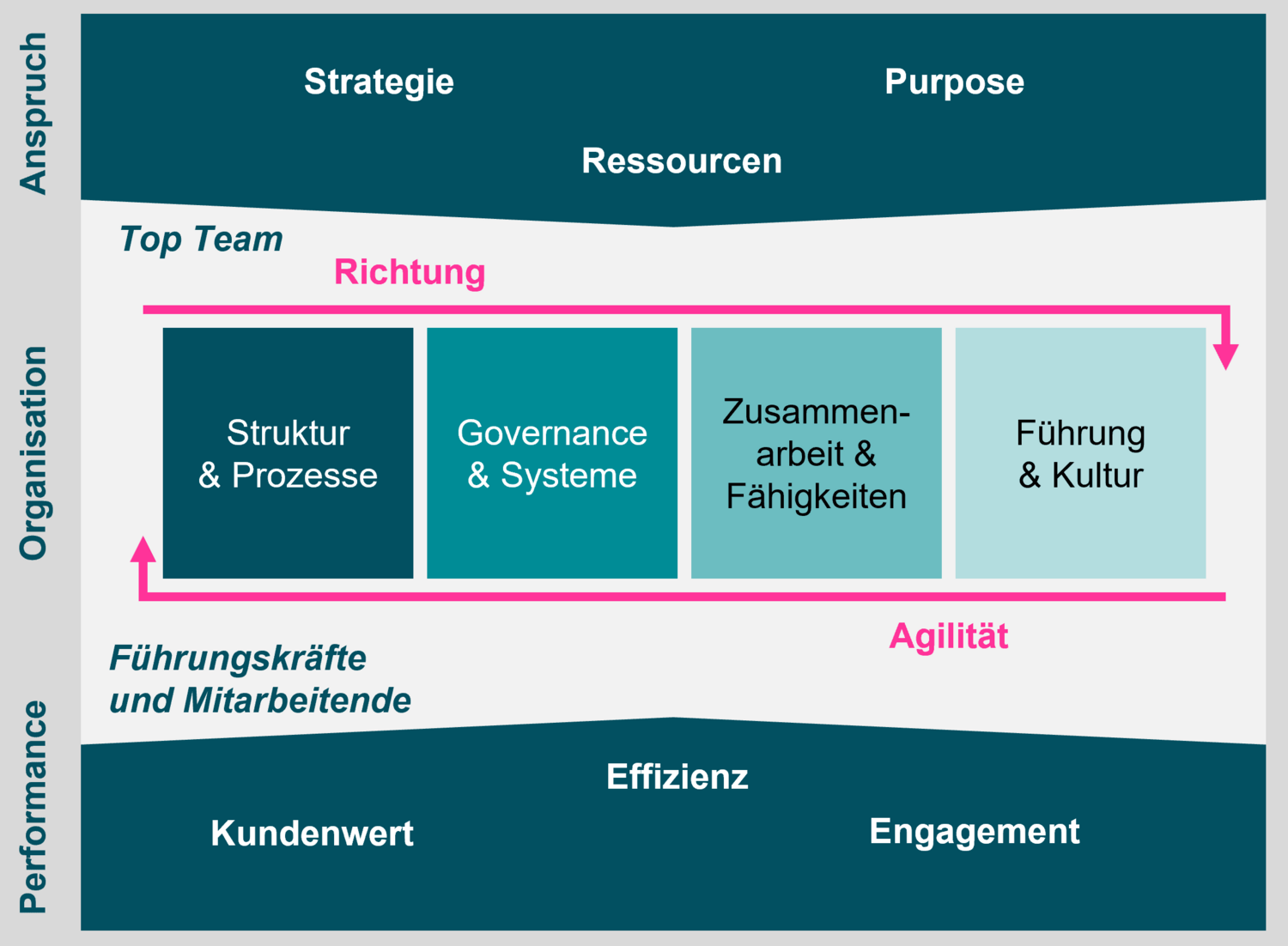

Beyond structure: Our view of organisations

We firmly believe that the right organisational structure must interact with the right processes. Both make up the formal side of an organisation, in which the set-up, processes and key decision-making rules are defined.

We are convinced that "softer" issues such as the quality of leadership and collaboration, trust and a shared focus are just as important and have been brought back into the spotlight from an agile perspective.

In addition, organisations are not an end in themselves, but always serve an overarching strategic ambition. "What should be improved?" is the key question at the beginning of every organisational change - and not always easy to answer. Nevertheless, a clear improvement goal is necessary because the quality of organisations is ultimately measured by their ability to deliver the required performance in the best possible way. By performance, we mean the value contribution both externally (on the markets and with the company's customers) and internally (for employees). In the long term, market and employee success go hand in hand.

How we develop organisational structures and organisations: Case study

One example of the development of new organisational structures while taking agile approaches into account is the fundamental transformation that a financial services provider mastered with our help. The company was originally organised into highly entrepreneurial national companies that were barely integrated. With our support, the company has created a uniform Europe-wide organisation with optimally integrated functions and product lines.

Our approach

The company's previously developed new strategy contained ambitious targets for growth and profitability, which could not be realised in the traditional structure of less integrated national companies. Instead, an organisation had to be developed that would enable functioning, overarching collaboration between strong product lines organised across Europe on the one hand and functions (tech/IT, sales) that were also integrated across Europe on the other - which in turn required the development of powerful digital platforms.

The result is a hybrid form of organisation that combines both classic and agile methods: on the one hand, functions have been integrated across Europe and are linked to the BUs (product lines), which also operate across Europe, as part of a matrix organisation. Cross-functional teams with flat hierarchies were created at the neuralgic interfaces, which work together using agile approaches. In this way, maximum flexibility and adaptability were achieved. This applies in particular to the neuralgic interface between IT or tech and the BUs, which is crucial to the success of a company that increasingly wants to develop digital platforms for digital business models.

This completely new organisational structure was developed as part of a transparent and participatory process. Top management worked closely with the top 50 employees.

The most important phases along the way

Phase 1 (duration: 1 month)

Together with the client, we formulated the design principles for the new structural organisation based on the top management strategy. The choice fell on a matrix organisation with cross-functional teams.

Together with the client, we derived the basic logic of a three-dimensional matrix from this. The key axes in this matrix were functions and BUs.

Phase 2 (3 months)

On this basis, we took care of the individual design of the BUs and FUs. For regulatory and labour law reasons in particular, the previous national companies remained in place, but were more organisational shells than business-relevant organisational units. In the first step, we developed an MVP (minimum viable product) for the new organisation: an organisation that already works, but still requires further detailed improvements and adjustments. This allowed us to reduce the complexity, keep the pace high and enable practical learning in the real operation of the MVP (instead of investing further time in ultimately theoretical concept explanations).

Particularly important here: the clear logic in the detailing of the unit profiles, starting with the BUs. In addition, the FUs (and then also the national companies) were empowered to define their organisation accordingly.

In order to make the creation of new structures as simple as possible, we clarified important interfaces with those involved during the process. In this way, we took the first step towards implementation. At the end of the process, top management took control.

Phase 3 (6 months)

After personalisation, i.e. the assignment of employees to the newly created or redesigned organisational units, the structured optimisation of the MVP took place. Work on details and improvements was carried out in a targeted manner and in close consultation with the client's management.

Under our guidance, the client transformed its business units and culture, laying the foundations for a new organisation that can react flexibly and appropriately to future challenges.

Conclusion: What can this mean for you?

- Structural organisations are an indispensable component, even in modern forms of organisation.

- The simple representation of an organisation as a structural organisation ("organigram") is helpful, but must not be misunderstood as an exhaustive depiction.

- The structural view and the process view complement each other - the intelligent confrontation of both perspectives helps in the design of more efficient organisations (e.g. in the clear design of their interfaces).

- An integrated structure and process view, i.e. the rule-based view of organisations, should also be supplemented by the no less important behaviour-based view of organisations. Organisations are not machines, but also social contexts.

- In our experience, agile approaches can complement these traditional concepts very effectively and increase the adaptability of organisations, but they are not a panacea in themselves.

The quality of organisations is a decisive factor in the successful implementation of intelligent strategies and the creation of added value for customers and employees. Significant changes in a company's markets often require new strategies - but always organisational changes and adjustments.

Shaping your own organisation is probably one of the most complex and challenging tasks for a company. We would be delighted to support you in this endeavour.

Axel Sauder, Partner in our Berlin office, will be happy to assist you with his comprehensive organisational expertise. Contact us or book an appointment directly, we look forward to hearing from you!